What does the Patriotic War of 1812 mean? Mozhaisk Deanery. Foreign campaign of the Russian army

The First World War broke out in 1612, when the Russian people's militia defeated the Polish occupation forces. The result is the preservation of the Russian state and the choice of a new royal dynasty, boyars Romanov.

The Second Patriotic War began two hundred years later - in June 1812, and also became victorious for Russia. Napoleon was defeated, Russia received new territories and new experience of the army elite. The result was the December uprising on Senate Square. Slavery was held for another 50 years.

And the third World War II - World War II 1939-1945. In Russian history it is accepted as the Great Patriotic War. The result is a victory over fascist Germany and the division of Europe into two camps - pro-communist and capitalist. Creation of the "iron curtain" for 50 years.

Half-forgotten Patriotic War

Unlike the Great Patriotic War, the war of 1812 was completed in less than a year. Beginning in June, already in December of the same 1812, the victory of Russia and the entry of Russian troops into the territory of the Napoleonic Empire was announced. On December 25, the day of the Nativity of Christ, the Manifesto on the expulsion of the French from Russia was issued.

“The club of the people's war rose with all its formidable and majestic strength and rose, fell and nailed the French until the entire invasion had perished,” wrote L.N. Tolstoy, emphasizing the popular character of the war.

This small, even by the standards of an individual, time period contains many great events.

June

By June 1812 French troops were ready to invade Russia. At the borders was a well-trained, mobilized army with extensive military experience, numbering, according to French data, in the first echelon of 448,000 men. Later, about 200 thousand more were sent to Russia - in total, according to Russian data, at least 600 thousand people.

On the night of 12 (24) June 1812the French army invaded Russia. Early in the morning the vanguard of the French troops entered the city of Kovno. Russian troops withdrew without accepting the battle.

The French army began a rapid advance into the interior of the country, seeking to cut off the Russian armies from each other and defeat them one by one.

July

July 22 (August 3) 1812army Barclay de Tolly and Bagration connected at Smolensk. This was a major success for the Russian army and the failure of Napoleon, who was striving to defeat the 1st and 2nd armies one by one and to a general border battle. The immediate task of the Russian command was solved - the mistakes of the strategic deployment of the Russian army were overcome.

August

The retreat of the Russian army. Having repulsed the fierce attacks of the stormed enemy columns, the Russian troops left the burning Smolensk on the night of August 6 (18) and continued their retreat. "The campaign of 1812 is over," said Napoleon, entering Smolensk.

8 (20) August 1812 the order of appointment was signed M.I. Kutuzov Commander-in-Chief. Companion P.A. Rumyantsevaand A.V. Suvorov was 67 years old.

September

The battle of Borodino, which lasted about 12 hours, began in the early morning August 26 / September 7. In the course of many hours of continuous battle, the French units failed to break through the defenses of the Russian troops. They stopped fighting and were withdrawn to their original positions.

Napoleon failed to defeat the Russian army. Kutuzov failed to defend Moscow. But here, on the Borodino field, the Napoleonic army, in fair judgment L.N. Tolstoy, received a "fatal wound".

The losses on both sides were colossal: the French lost about 35 thousand people at Borodino, the Russians - 45 thousand. Napoleonic generals demanded new reinforcements, but the reserves were fully used, and the emperor did not put the old guard into operation.

In the Battle of Borodino, the best enemy forces were defeated, thanks to which the transfer of the initiative into the hands of the Russian army was prepared.

Napoleon later said this about the Battle of Borodino: “Of all my battles, the most terrible is the one that I gave near Moscow. The French in it showed themselves worthy to win, and the Russians acquired the right to be invincible. "

2 (14) September 1812 Napoleon approached Moscow and stopped at Poklonnaya Hill. He waited a long time for this day, confident that the capture of Moscow would make further resistance to Russia meaningless. For more than two hours Napoleon waited for the Moscow deputation with the keys to the city. And then he was told that the city was empty.

Soon the city was set on fire by the Great Moscow Fire. The Moscow fire and looting soon destroyed the food supplies in the city. The resistance of the Russian army to the enemy grew, the partisan movement expanded.

From Moscow Napoleon offered three times Alexander I start negotiations for peace. The royal court and officials close to Alexander I ( A.A. Arakcheev, N.P. Rumyantsev, HELL. Balashov) were advised to sign the peace. But the king was adamant: all Napoleon's letters remained unanswered.

In such a situation, further stay in Moscow for the French army became dangerous.

October

October 7/19, after 36 days of fruitless efforts to achieve peace with Russia, Napoleon ordered a retreat from Moscow. As he left, he ordered to blow up the Kremlin. As a result of the explosion, the Faceted Chamber and other buildings burned down. Only the courage of the heroes, who cut the lit fuses, and the rain that began, saved the ancient monument of Russian culture from complete destruction.

6 (18) October 1812murat's corps, directed by Napoleon to the r. Chernishna to monitor the Russian army, was attacked by Kutuzov. As a result of the fighting, the French lost about 5 thousand people and were forced to retreat. This was the first victory of the Russian army's offensive that had begun.

“Our retreat, which began with a masquerade,” wrote a French officer E. Labom, - ended with a funeral procession. "

November

Mid November the main forces of Kutuzov defeated the enemy in three-day battles near the town of Krasny. Napoleon's army had to cross the Berezina River to break out of Russia. 20-30 thousand people managed to cross the Berezina, more than 20 thousand died during the crossing or were captured.

After the Berezina, Napoleon's retreat turned into a disorderly flight. His Great Army practically ceased to exist. A little more than 30 thousand people remained from it.

In the end of November the emperor from the town of Smorgon went to France. On December 6 (18) he was in Paris. ...

On December 25, the day of the Nativity of Christ, the Manifesto on the expulsion of the French from Russia was issued.

What did the Patriotic War mean for Russia 100 years ago?

Emphasizing the scale of the events, the publicist Alexander Herzen believed that the true history of Russia begins in 1812: until that time there was only its prehistory.

“The interval between 1810 and 1820 is not long,” wrote A.I. Herzen. - But between them is 1812. The morals are the same; the landlords who returned from their villages to the burnt capital are the same. But something has changed. A thought flashed through, and what she touched with her breath was no longer what it was.

The future Decembrists highly appreciated the significance of the Patriotic War of 1812 and the foreign campaign, considering themselves "children of 1812". "Napoleon invaded Russia," he remarked A. Bestuzhev- and then the Russian people for the first time felt their strength, then it was then that a feeling of independence, first patriotic, and later popular, awakened in all hearts. This is the beginning of free thought in Russia. "

Ilya Kudryashov, an employee of the Borodino Battle panorama museum, scientific consultant of the project dedicated to the war of 1812, which Gazeta.Ru prepared together with the historical website Runivers, answered the question of Gazeta RU:

- How, according to your estimates, is the celebration of the anniversary now and a hundred years ago?

- A hundred years ago we celebrated one of the brightest events in the history of that Russia. Then on the throne was a monarch from the same dynasty (Alexander I was the elder brother of his great-grandfather Nicholas II). There were the same regiments that fought on the Borodino field, and they erected monuments at their own expense.

Now the tradition has been interrupted, this is just another jubilee occasion to remember about patriotism, to renovate museums and hold events for show.

What do we remember about the war of 1812?

The Public Opinion Foundation invited the Russians to answer the question of the Unified State Exam on the history of the war of 1812: choose a battle that relates to the war with Napoleon. Only 13% of the respondents made the right choice.

Less than a third of our fellow citizens know who was the emperor of Russia during this war.

The majority of respondents (17%) associate the words "Patriotic War of 1812" with Napoleon. “Holy war”, “we fought with the French,” - this is how 12% of respondents answered.

9% of respondents feel pride for the country, for the people who defended the Fatherland.

This war is associated with the Battle of Borodino by 9% of survey participants, 8% - with the commander Mikhail Kutuzov.

The victory over the French was said by 3% of the respondents. To the question with whom Russia fought in 1812, 69% of the survey participants answered correctly, 26% found it difficult to answer, and 5% of the respondents were mistaken.

Moreover, most often the wrong answer was given by people aged 18-30. And in the group of 80 and older there were no mistakes, although 52% of the respondents found it difficult to answer.

About who was the Russian emperor during the Patriotic War of 1812, 29% of respondents recalled. Found it difficult to answer 51%, 7% each believe that at that time Russia was ruled or Paul I, or Nicholas I, and 6% even mentioned the name Catherine II.

And he invaded Russian lands. The French rushed on the offensive like a bull during a bullfight. Napoleon's army included a European hodgepodge: in addition to the French, there were also (forcibly recruited) Germans, Austrians, Spaniards, Italians, Dutch, Poles and many others, totaling up to 650 thousand people. Russia could have fielded about the same number of soldiers, but some of them, together with Kutuzovwas still in Moldova, the other part in the Caucasus. During the invasion of Napoleon, up to 20 thousand Lithuanians joined his army.

The Russian army was split into two lines of defense, under the command of a general Peter Bagration and Michael Barclay de Tolly... The invasion of the French fell on the troops of the latter. Napoleon's calculation was simple - one or two victorious battles (maximum - three), and Alexander I will be forced to sign a peace on French terms. However, Barclay de Tolly gradually, with minor skirmishes, retreated deep into Russia, but did not enter the main battle. Near Smolensk, the Russian army almost fell into an encirclement, but did not enter the battle and eluded the French, continuing to drag them deep into its territory. Napoleon occupied the deserted Smolensk and could stop there for now, but Kutuzov, who arrived in time from Moldavia to replace Barclay de Tolly, knew that the French emperor would not do that, and continued his retreat to Moscow. Bagration was eager to attack, and the majority of the country's population supported him, but Alexander did not allow, leaving Peter Bagration on the border in Austria in case of an attack by the allies of France.

Along the way, Napoleon got only abandoned and burned out settlements - no people, no supplies. After the "show" battle for Smolensk on August 18, 1812, Napoleon's troops began to get tired of russian campaign of 1812because the conquest was somehow negative: there were no large-scale battles and high-profile victories, there were no trophy supplies and weapons, winter was approaching, during which the “Great Army” had to spend the winter somewhere, and nothing suitable for quartering was captured.

Battle of Borodino.

At the end of August, near Mozhaisk (125 kilometers from Moscow), Kutuzov stopped in a field near the village Borodinowhere he decided to give a general battle. For the most part, he was forced by public opinion, since the constant retreat did not correspond to the moods of either the people, or the nobles, or the emperor.

On August 26, 1812, the famous Battle of Borodino. Bagration pulled himself up to Borodino, but the Russians were still able to deploy just over 110 thousand soldiers. Napoleon at that time had up to 135 thousand people.

The course and result of the battle are known to many: the French repeatedly stormed the defensive redoubts of Kutuzov with the active support of artillery ("Horses, people mixed up in a heap ..."). Hungry for a normal battle, the Russians heroically repelled the attacks of the French, despite the enormous superiority of the latter in weapons (from rifles to cannons). The French lost up to 35 thousand killed, and the Russians ten thousand more, but Napoleon only managed to slightly displace the central positions of Kutuzov, and in fact, Bonaparte's attack was stopped. After the battle, which lasted all day, the French emperor began to prepare for a new assault, but Kutuzov, by the morning of August 27, withdrew his troops to Mozhaisk, not wanting to lose even more people.

On September 1, 1812 in a nearby village there was a military council in Filiduring which Mikhail Kutuzov with the support of Barclay de Tolly decided to leave Moscow in order to save the army. Contemporaries say that this decision was extremely difficult for the commander-in-chief.

On September 14, Napoleon entered the abandoned and devastated recent capital of Russia. During his stay in Moscow, sabotage groups of the Moscow governor Rostopchin repeatedly attacked French officers and burned their seized apartments. As a result, from 14 to 18 September Moscow was on fire, and Napoleon did not have enough resources to cope with the fire.

At the beginning of the invasion, before the Battle of Borodino, and also three times after the occupation of Moscow, Napoleon tried to negotiate with Alexander and sign peace. But from the very beginning of the war, the Russian emperor adamantly forbade any negotiations while enemy feet trample on Russian soil.

Realizing that it would not be possible to spend the winter in ruined Moscow, on October 19, 1812, the French left Moscow. Napoleon decided to return to Smolensk, not by a scorched path, but through Kaluga, hoping to get at least some supplies along the way.

In the battle at Tarutino and a little later at Maly Yaroslavets on October 24, Kutuzov fought off the French, and they were forced to return to the devastated Smolensk road, which they had previously followed.

On November 8, Bonaparte reached Smolensk, which was ruined (and half by the French themselves). All the way to Smolensk, the emperor was constantly losing man after man - up to hundreds of soldiers a day.

During the summer-autumn of 1812, an unprecedented partisan movement was formed in Russia, leading the liberation war. Partisan detachments numbered up to several thousand people. They attacked Napoleon's army, like Amazonian piranhas on a wounded jaguar, waited for convoys with supplies and weapons, destroyed the vanguards and rearguards of the troops. The most famous leader of these units was Denis Davydov... Peasants, workers and nobles alike joined the partisan detachments. It is believed that it was they who destroyed more than half of Bonaparte's army. Of course, the soldiers of Kutuzov did not lag behind, who also pursued Napoleon on his heels and constantly made sorties.

On November 29, a major battle took place on the Berezina, when admirals Chichagov and Wittgenstein, without waiting for Kutuzov, attacked Napoleon's army and destroyed 21 thousand of his soldiers. However, the emperor was able to slip away, with only 9 thousand people left at his disposal. With them, he reached Vilna (Vilnius), where his generals Ney and Murat were waiting for him.

On December 14, after Kutuzov's attack on Vilna, the French lost 20 thousand soldiers and abandoned the city. Napoleon fled in haste to Paris, ahead of the rest of his The great army... Together with the remnants of the garrison of Vilna and other cities, a little more than 30 thousand Napoleonic warriors left Russia, while at least 610 thousand invaded Russia.

After the defeat in Russia French empire began to fall apart. Bonaparte continued to send ambassadors to Alexander, offering almost all of Poland in exchange for a peace treaty. Nevertheless, the Russian emperor decided to completely rid Europe of dictatorship and tyranny (and these are not loud words, but reality) Napoleon Bonaparte.

Research by Archpriest Alexander Ilyashenko "Dynamics of the number and losses of the Napoleonic army in the Patriotic War of 1812".

2012 marks two hundred years Patriotic War of 1812 and Borodino battle... These events are described by many contemporaries and historians. However, despite many published sources, memoirs and historical studies, there is no established point of view either for the size of the Russian army and its losses in the Battle of Borodino, or for the number and losses of the Napoleonic army. The range of values \u200b\u200bis significant both in the number of armies and in the amount of losses.

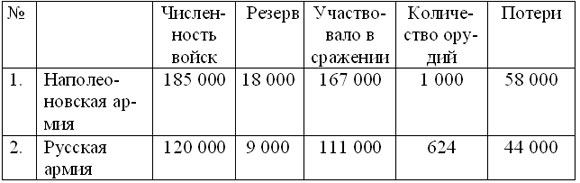

In the "Military Encyclopedic Lexicon" published in St. Petersburg in 1838 and in the inscription on the Main Monument erected on the Borodino field in 1838, it is recorded that under Borodino there were 185 thousand Napoleonic soldiers and officers against 120 thousand Russians. The monument also indicates that the losses of the Napoleonic army amounted to 60 thousand, the losses of the Russian - 45 thousand people (according to modern data, respectively - 58 and 44 thousand).

Along with these estimates, there are others that are radically different from them.

So, in the bulletin No. 18 of the "Great" army, issued immediately after the Battle of Borodino, the emperor of France defined the losses of the French as only 10 thousand soldiers and officers.

The spread of estimates is clearly demonstrated by the following data.

Table 1. Estimates of the opposing forces made at different times by various authors

Estimates of the sizes of opposing forces made at different times by different historians

Tab. 1

A similar picture is observed for the losses of the Napoleonic army. In the table below, the losses of the Napoleonic army are presented in ascending order.

Table 2. Losses of the Napoleonic army, according to historians and participants in the battle

Tab. 2

As we can see, indeed, the range of values \u200b\u200bis quite large and amounts to several tens of thousands of people. In table 1, the data of the authors, who considered the size of the Russian army to be superior to that of Napoleon, are highlighted in bold. It is interesting to note that Russian historians have joined this point of view only since 1988, i.e. since the beginning of perestroika.

The most widespread for the number of Napoleon's army was 130,000, for the Russian - 120,000, for losses, respectively - 30,000 and 44,000.

As P.N. Grunberg, beginning with the work of General MI Bogdanovich "History of the Patriotic War of 1812 according to reliable sources", is recognized for the reliable number of troops of the Great Army at Borodino, proposed back in the 1820s. J. de Chambray and J. Pele de Clozo. They were guided by the roll call data in Gzhatsk on September 2, 1812, but ignored the arrival of reserve units and artillery, which had replenished Napoleon's army before the battle.

Many modern historians reject the data indicated on the monument, and some researchers even arouse irony. So, A. Vasiliev in his article “Losses of the French Army at Borodino” writes that “unfortunately, in our literature about the Patriotic War of 1812, the figure of 58,478 people is very often found. It was calculated by the Russian military historian V.A.Afanasyev based on data published in 1813 by order of Rostopchin. The calculations are based on the information of the Swiss adventurer Alexander Schmidt, who deserted to the Russians in October 1812 and passed himself off as a major, allegedly serving in the personal office of Marshal Berthier. " One cannot agree with this opinion: "General Count Toll, based on official documents captured from the enemy during his flight from Russia, counts 185,000 people in the French army and up to 1,000 pieces of artillery."

The command of the Russian army had the opportunity to rely not only on "official documents captured from the enemy during his flight from Russia", but also on the information of captured enemy generals and officers. For example, General Bonami was captured in the Battle of Borodino. British General Robert Wilson, who served with the Russian army, wrote on December 30, 1812: “There are at least fifty generals among our prisoners. Their names have been published and will undoubtedly appear in British newspapers. "

These generals, as well as the captured officers of the General Staff, had reliable information. It can be assumed that it was on the basis of numerous documents and testimonies of captured generals and officers, hot on the heels of domestic military historians, that the true picture of events was restored.

Based on the facts available to us and their numerical analysis, we tried to estimate the number of troops that Napoleon led to the Borodino field, and the loss of his army in the Battle of Borodino.

Table 3 shows the strength of both armies in the Battle of Borodino according to a widespread point of view. Modern Russian historians estimate the loss of the Russian army at 44,000 soldiers and officers.

Table 3. The number of troops in the battle of Borodino

Tab. 3

At the end of the battle, reserves remained in each army, which did not directly participate in it. The number of troops of both armies directly participating in the battle, equal to the difference in the total number of troops and the size of reserves, practically coincides, in terms of artillery, the Napoleonic army was inferior to the Russian. The losses of the Russian army are one and a half times greater than the losses of the Napoleonic one.

If the proposed picture corresponds to reality, then what is Borodin's day glorious for? Yes, of course, our soldiers fought bravely, but the enemy is braver, ours are skillful, and they are more skillful, our military leaders are experienced, and theirs are more experienced. So which army deserves more admiration? With this balance of power, the impartial answer is obvious. If we remain impartial, we will also have to admit that Napoleon won another victory.

True, some bewilderment arises. Of the 1,372 guns that were in the army that crossed the border, about a quarter were assigned to auxiliary sectors. Well, of the remaining more than 1,000 guns to the Borodino field, only slightly more than half were delivered?

How could Napoleon, who deeply understood the importance of artillery from a young age, allow not all the guns, but only some of them to be put up for the decisive battle? It seems absurd to accuse Napoleon of his uncharacteristic carelessness or inability to ensure the transportation of weapons to the battlefield. The question is, does the proposed picture correspond to reality and is it possible to put up with such absurdities?

Such puzzling questions are dispelled by data taken from the Monument installed on the Borodino field.

Table 4. The number of troops in the Battle of Borodino. Monument

Tab. 4

With such a balance of forces, a completely different picture emerges. Despite the glory of a great commander, Napoleon, possessing one and a half superiority in forces, not only could not crush the Russian army, but his army suffered losses by 14,000 more than the Russian. The day on which the Russian army withstood the onslaught of superior enemy forces and was able to inflict heavier losses on it than its own is undoubtedly a day of glory for the Russian army, a day of valor, honor, courage of its commanders, officers and soldiers.

In our opinion, the problem is of a fundamental nature. Or, using Smerdyakov's phraseology, in the Battle of Borodino, the "smart" nation defeated the "stupid" one, or the numerous forces of Europe united by Napoleon turned out to be powerless before the greatness of spirit, courage and martial art of the Russian Christian army.

In order to better imagine the course of the war, we present data characterizing its end. Prominent German military theorist and historian Karl Clausewitz (1780-1831), an officer in the Prussian army who fought in the 1812 war with the Russian army, described these events in the 1812 campaign to Russia, published in 1830 shortly before his death.

Drawing on Shaumbra, Clausewitz estimates the total number of Napoleonic forces that crossed the Russian border during the campaign at 610,000.

When the remnants of the French army gathered across the Vistula in January 1813, “it turned out that they number 23,000 people. The Austrian and Prussian troops returning from the campaign numbered approximately 35,000 people, therefore, together they amounted to 58,000 people. Meanwhile, the created army, including here and the troops that later approached, numbered in fact 610,000 people.

Thus, 552,000 people remained killed and captured in Russia. The army had 182,000 horses. Of these, including the Prussian and Austrian troops and the troops of MacDonald and Rainier, 15,000 survived, therefore, 167,000 were lost. The army had 1,372 guns; the Austrians, Prussians, MacDonald and Rainier brought back with them up to 150 guns, therefore, over 1200 guns were lost. "

The data given by Clausewitz are summarized in the table.

Table 5. Total losses of the "Great" army in the war of 1812

Tab. five

Only 10% of the personnel and equipment of the army, which proudly called itself "Great", returned back. History knows no such thing: an army more than two times superior to its enemy was utterly defeated by him and almost completely destroyed.

Emperor

Before proceeding directly to further research, let us touch on the personality of the Russian Emperor Alexander I, which has undergone a completely undeserved distortion.

The former French ambassador to Russia, Armand de Caulaincourt, a man close to Napoleon, who moved in the highest political spheres of the then Europe, recalls that on the eve of the war, in a conversation with him, the Austrian Emperor Franz said that Emperor Alexander

“They characterized him as an indecisive, suspicious and influenced sovereign; meanwhile, in matters that may entail such enormous consequences, one must rely only on oneself and, in particular, not go to war before all means of maintaining peace have been exhausted. "

That is, the Austrian emperor, who betrayed the alliance with Russia, considered the Russian emperor to be soft and dependent.

From school years, many people remember the words:

The ruler is weak and crafty,

Bald dandy, enemy of labor

Then he reigned over us.

This false idea of \u200b\u200bEmperor Alexander, launched at one time by the political elite of the then Europe, was uncritically perceived by liberal Russian historians, as well as the great Pushkin, and many of his contemporaries and descendants.

The same Caulaincourt preserved de Narbonne's story, characterizing the Emperor Alexander from a completely different perspective. De Narbonne was sent by Napoleon to Vilna, where the Emperor Alexander was.

“Emperor Alexander from the very beginning told him frankly:

- I will not draw my sword first. I do not want Europe to hold me responsible for the blood that will be shed in this war. I have been threatened for 18 months. French troops are on my borders, 300 leagues from their country. I am at my place for now. Fortifying and arming fortresses that almost touch my borders; send troops; incite the Poles. The emperor enriches his treasury and ruins individual unfortunate subjects. I stated that in principle I did not want to act in the same way. I do not want to take money from the pockets of my subjects to put it in my own pocket.

300 thousand French are preparing to cross my borders, and I still respect the union and remain faithful to all the obligations I have assumed. When I change course, I will do it openly.

He (Napoleon - author) just called Austria, Prussia and all of Europe to arms against Russia, and I am still loyal to the union - to such an extent my reason refuses to believe that he wants to sacrifice real benefits to the chances of this war. I do not create illusions for myself. I value his military talents too highly to ignore all the risks to which the lot of war may expose us; but if I have done everything to preserve an honorable peace and a political system that can lead to universal peace, then I will not do anything incompatible with the honor of the nation I rule. The Russian people are not one of those who retreat in the face of danger.

If all the bayonets of Europe are gathered on my borders, they will not force me to speak a different language. If I was patient and restrained, it was not because of weakness, but because it is the duty of the sovereign not to listen to the voices of discontent and to keep in mind only the calmness and interests of his people when it comes to such major issues, and when he hopes to avoid a struggle that might worth so many sacrifices.

Emperor Alexander told de Narbonne that at the moment he had not yet assumed any obligation contrary to the alliance, that he was confident in his righteousness and in the justice of his cause and would defend himself if attacked. In conclusion, he opened before him a map of Russia and said, pointing to the distant outskirts:

- If the Emperor Napoleon decided to go to war and fate is not favorable to our just cause, then he will have to go to the very end in order to achieve peace.

Then he repeated once more that he would not be the first to draw his sword, but that he would be the last to put it in its sheath. "

Thus, the Emperor Alexander, a few weeks before the start of hostilities, knew that a war was being prepared, that the invasion army already numbered 300 thousand people, led a firm policy, guided by the honor of the nation he ruled, knowing that “the Russian people are not one of those who retreat in the face of danger. " In addition, we note that the war with Napoleon is not a war with France only, but with a united Europe, since Napoleon "called Austria, Prussia and all of Europe to arms against Russia."

There was no question of any "treachery" and surprise. The leadership of the Russian Empire and the command of the army had extensive information about the enemy. On the contrary, Caulaincourt stresses that

“Prince Ekmühl, the General Staff and everyone else complained that they had not been able to obtain any information so far, and not a single intelligence officer had yet returned from that bank. There, on the other side, only a few Cossack patrols were visible. The Emperor inspected the troops in the afternoon and once again took up reconnaissance of the surroundings. The corps of our right flank knew no more of the enemy's movements than we did. There was no information about the position of the Russians. Everyone complained that not one of the spies was returning, which greatly annoyed the emperor. "

The situation did not change with the outbreak of hostilities.

“The king of Naples, who commanded the vanguard, often made day trips of 10 and 12 leagues. People did not leave the saddle from three in the morning until 10 in the evening. The sun, almost never descending from the sky, made the emperor forget that a day has only 24 hours. The vanguard was reinforced by carabinieri and cuirassiers; horses, like people, were exhausted; we lost a lot of horses; the roads were covered with horse corpses, but the emperor every day, every moment cherished the dream of overtaking the enemy. At any cost he wanted to get prisoners; this was the only way to get any information about the Russian army, since it could not be obtained through spies, who immediately ceased to bring us any benefit as soon as we found ourselves in Russia. The prospect of the whip and Siberia froze the ardor of the most skillful and most fearless of them; to this was added the real difficulty of penetrating the country, and especially into the army. Information was received only through Vilno. Nothing came directly. Our marches were too long and too fast, and our too exhausted cavalry could not send out reconnaissance detachments or even flank patrols. Thus, the emperor most often did not know what was happening two leagues from him. But no matter what price was attached to the capture of prisoners, it was not possible to capture them. The Cossacks had a better guard than ours; their horses, which enjoyed better care than ours, turned out to be more resilient when attacking, the Cossacks attacked only when the opportunity arises and never got involved in battle.

By the end of the day our horses were usually so tired that the smallest collision cost us a few brave men, as their horses lagged behind. When our squadrons retreated, one could observe how the soldiers dismounted in the midst of the battle and pulled their horses behind them, while others were even forced to abandon their horses and flee on foot. Like everyone else, he (the emperor - author) was surprised by this retreat of the 100,000-strong army, in which there was not a single laggard, not a single cart. For 10 leagues around it was impossible to find any horse to guide. We had to put guides on our horses; often it was not even possible to find a person who would serve as a guide to the emperor. It happened that the same guide led us three or four days in a row and, in the end, ended up in an area that he knew no better than us.

While the Napoleonic army followed the Russian, unable to obtain even the most insignificant information about its movements, MI Kutuzov was appointed commander-in-chief of the army. On August 29, he "arrived at the army in Tsarevo-Zaymishche, between Gzhatsk and Vyazma, and the Emperor Napoleon did not yet know about it."

This testimony of de Caulaincourt is, in our opinion, a special praise for the unity of the Russian people, so striking that no intelligence and enemy espionage was possible!

Now we will try to trace the dynamics of the processes that led to such an unprecedented defeat. The campaign of 1812 naturally falls into two parts: the offensive and the retreat of the French. We will only consider the first part.

According to Clausewitz, "The war is fought in five separate theaters of war: two to the left of the road leading from Vilna to Moscow make up the left wing, two on the right make up the right wing, and the fifth is the huge center itself." Clausewitz goes on to write that:

1. Napoleonic Marshal MacDonald on the lower reaches of the Dvina with an army of 30,000 oversees the Riga garrison, numbering 10,000.

2. Along the middle reaches of the Dvina (in the Polotsk region), first Oudinot with 40,000 men, and later Oudinot and Saint-Cyr with 62,000 against the Russian general Wittgenstein, whose forces at first reached 15,000, and later 50,000.

3. In southern Lithuania, Schwarzenberg and Rainier with 51,000 men were located in front of the Pripyat swamps, against General Tormasov, who was later joined by Admiral Chichagov with the Moldavian army, only 35,000 people.

4. General Dombrovsky with his division and a small number of cavalry, only 10,000 men, oversees Bobruisk and General Gertel, who are forming a reserve corps of 12,000 people near the city of Mozyr.

5. Finally, in the middle are the main forces of the French, numbering 300,000, against the two main Russian armies, Barclay and Bagration, with a force of 120,000; these French forces are directed to Moscow to conquer it.

Let us summarize the data given by Clausewitz in a table and add the column "The ratio of forces".

Table 6. Distribution of forces by directions

Tab. 6

With more than 300,000 soldiers in the center against 120,000 Russian regular troops (Cossack regiments do not belong to regular troops), that is, having an advantage of 185,000 people at the initial stage of the war, Napoleon sought to defeat the Russian army in a general battle. The deeper he penetrated deep into the territory of Russia, the more acute this need became. But the persecution of the Russian army, exhausting for the center of the "Great" army, contributed to an intensive reduction in its numbers.

The fierceness of the Borodino battle, its bloodyness, as well as the scale of losses can be judged from the fact that cannot be ignored. Domestic historians, in particular, employees of the museum on the Borodino field, estimate the number of people buried in the field at 48-50 thousand people. And in total, according to the military historian General A. I. Mikhailovsky-Danilevsky, 58,521 bodies were buried or burned in the Borodino field. We can assume that the number of bodies buried or burned is equal to the number of soldiers and officers of both armies who died and died from wounds in the Battle of Borodino.

The data of the French officer Denier who served as an inspector at the General Staff of Napoleon, presented in Table 7, were widely spread about the losses of the Napoleonic army in the Battle of Borodino:

Table 7. Losses of the Napoleonic army.

Tab. 7

Denier figures, rounded up to 30 thousand, are currently considered the most reliable. Thus, if we accept that Denier's data are correct, then the share of the losses of the Russian army will only have to be killed

58,521 - 6,569 \u003d 51,952 soldiers and officers.

This value significantly exceeds the value of the losses of the Russian army, equal, as mentioned above, 44 thousand, including the killed and wounded and prisoners.

Denier's data is also questionable for the following reasons.

The total losses of both armies at Borodino amounted to 74 thousand, including a thousand prisoners on each side. Subtract from this value the total number of prisoners, we get 72 thousand killed and wounded. In this case, both armies will have only

72,000 - 58,500 \u003d 13,500 wounded,

This means that the ratio between wounded and killed will be

13 500: 58 500 = 10: 43.

Such a small number of wounded in relation to the number of those killed seems completely implausible.

We are faced with clear contradictions with the available facts. The losses of the "Great" army in the Battle of Borodino, equal to 30,000 people, are obviously underestimated. We cannot consider this amount of losses realistic.

We will proceed from the assumption that the losses of the "Great" army amount to 58,000 people. Let's estimate the number of killed and wounded in each army.

According to Table 5, in which Denier's data are given, 6,569 were killed in the Napoleonic army, 21,517 were wounded, 1,176 officers and soldiers were captured (the number of prisoners is rounded to 1,000). Russian soldiers were also captured about a thousand people. Let us subtract from the number of losses of each army the number of those taken prisoner, we get 43,000 and 57,000 people, respectively, in the amount of 100 thousand. Let's assume that the number of people killed is proportional to the amount of losses.

Then, in the Napoleonic army died

57,000 58,500 / 100,000 \u003d 33,500,

wounded

57 000 – 33 500 = 23 500.

Perished in the Russian army

58 500 - 33 500 = 25 000,

wounded

43 000 – 25 000 = 18 000.

Table 8. Losses of the Russian and Napoleonic armies

in the battle of Borodino.

Tab. 8

Let's try to find additional arguments and, with their help, substantiate the realistic value of the losses of the "Great" army in the Battle of Borodino.

In our further work, we relied on an interesting and very original article by I.P. Artsybashev "Losses of Napoleon's generals on September 5-7, 1812 in the Battle of Borodino." After conducting a thorough study of the sources, I.P. Artsybashev established that in the Borodino battle, not 49, as is commonly believed, were out of action, but 58 generals. This result is confirmed by the opinion of A. Vasiliev, who writes in this article: "The Battle of Borodino was marked by large losses of generals: 26 generals were killed and wounded in the Russian troops, and 50 in Napoleon's (according to incomplete data)."

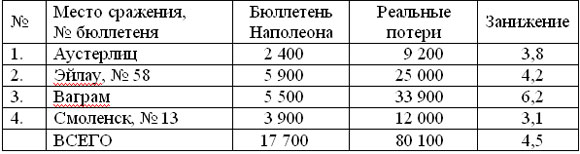

After the battles given to him, Napoleon published bulletins containing information about the size and losses of his and the enemy army so far from reality that in France a saying arose: "Lies like a bulletin."

1. Austerlitz. The Emperor of France acknowledged the loss of the French: 800 killed and 1,600 wounded, a total of 2,400 people. In fact, the losses of the French amounted to 9,200 soldiers and officers.

2. Eylau, 58th bulletin. Napoleon ordered the publication of data on the losses of the French: 1,900 killed and 4,000 wounded, only 5,900 people, while the actual losses amounted to 25,000 soldiers and officers killed and wounded.

3. Wagram. The emperor agreed to a loss of 1,500 killed and 3,000-4,000 wounded French. Total: 4,500-5,500 soldiers and officers, but in fact 33,900.

4. Smolensk. 13th Bulletin of the "Great Army". Losses of 700 French killed and 3,200 wounded. Total: 3,900 people. In fact, the losses of the French amounted to over 12,000 people.

We will summarize the given data in a table

Table 9. Napoleon's bulletins

Tab. nine

The average underestimation for these four battles is 4.5, therefore, it can be assumed that Napoleon underestimated the losses of his army more than four times.

"A lie must be monstrous in order to be believed," - said at one time the Minister of Propaganda of Nazi Germany, Dr. Goebbels. Looking at the table above, one has to admit that he had famous predecessors, and he had someone to learn from.

Of course, the accuracy of this estimate is not high, but since Napoleon said that his army at Borodino lost 10,000 men, it can be assumed that the actual losses were about 45,000 people. These considerations are of a qualitative nature, we will try to find more accurate estimates on the basis of which we can draw quantitative conclusions. For this we will rely on the ratio of generals and soldiers of the Napoleonic army.

Consider the well-described battles of the empire of 1805-1815, in which the number of Napoleonic generals who were out of action was more than 10.

Table 10. Losses of out-of-action generals and out-of-action soldiers

Tab. ten

On average, there are 958 soldiers and officers who are out of action for every general who is out of action. This is a random variable, its variance is 86. We will proceed from the fact that in the Battle of Borodino, there were 958 ± 86 soldiers and officers who were out of action for one general who was out of action.

958 58 \u003d 55 500 people.

The variance of this quantity is

86 58 \u003d 5,000.

With a probability of 0.95, the true value of the losses of the Napoleonic army lies in the range from 45,500 to 65,500 people. The amount of losses of 30-40 thousand lies outside this interval and, therefore, is statistically insignificant and can be discarded. On the contrary, a loss value of 58,000 lies within this confidence interval and can be considered significant.

As we moved deeper into the territory of the Russian Empire, the size of the “Great” army was greatly reduced. Moreover, the main reason for this was not combat losses, but losses caused by the exhaustion of people, lack of sufficient food, drinking water, hygiene and sanitation and other conditions necessary to support the march of such a large army.

Napoleon's goal was in a rapid campaign, using the superiority of forces and his own outstanding military leadership, to defeat the Russian army in a general battle and from a position of strength to dictate his terms. Contrary to expectations, it was not possible to impose a battle, because the Russian army maneuvered so skillfully and set such a pace of movement that the “Great” army could withstand with great difficulty, experiencing hardships and needing everything necessary.

The principle of "war feeds itself", which proved itself well in Europe, turned out to be practically inapplicable in Russia with its distances, forests, swamps and, most importantly, a rebellious population that did not want to feed the enemy army. But Napoleonic soldiers suffered not only from hunger, but also from thirst. This circumstance did not depend on the wishes of the neighboring peasants, but was an objective factor.

Firstly, in contrast to Europe, settlements in Russia are quite far from each other. Secondly, there are as many wells in them as is necessary to meet the needs of residents in drinking water, but absolutely not enough for many passing soldiers. Thirdly, the Russian army was in front, the soldiers of which drank these wells “to the mud,” as he writes in the novel War and Peace.

The lack of water also led to an unsatisfactory sanitary condition of the army. This entailed fatigue and exhaustion of the soldiers, caused their diseases, as well as the death of horses. All this taken together entailed significant non-combat losses of the Napoleonic army.

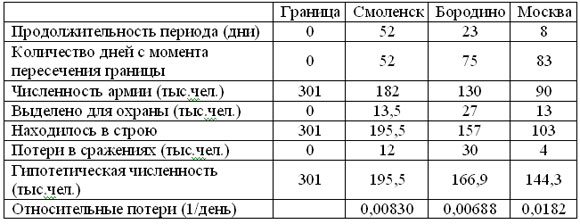

We will consider the change over time in the size of the center of the "Great" army. The table below uses Clausewitz's data on army size changes.

Table 11. The size of the "Great" army

Tab. eleven

In the column "Number" of this table, based on Clausewitz's data, the number of soldiers of the center of the "Great" army at the border, on the 52nd day near Smolensk, on the 75th near Borodino and on the 83rd at the time of entry into Moscow is presented. To ensure the security of the army, as noted by Clausewitz, detachments were allocated to guard communications, flanks, etc. The number of soldiers in the ranks is the sum of the two previous values. As you can see from the table, on the way from the border to the Borodino field, the "Great" army lost

301,000 - 157,000 \u003d 144,000 people,

that is, slightly less than 50% of its initial population.

After the Battle of Borodino, the Russian army retreated, the Napoleonic army continued its pursuit. The fourth corps, under the command of the Viceroy of Italy, Eugene Beauharnais, moved through Ruza to Zvenigorod in order to get on the path of the retreat of the Russian army, detain it and force it to accept a battle with the main forces of Napoleon in unfavorable conditions. The detachment of Major General F.F. Wincengerode detained the viceroy's corps for six hours. Russian troops occupied the hill, resting their right flank against a ravine, and with their left flank against a swamp. The slope facing the enemy was a plowed field. Natural obstacles on the flanks, as well as loose ground, hampered the maneuver of enemy infantry and cavalry. A well-chosen position allowed the small detachment "to offer vigorous resistance, which cost the French several thousand killed and wounded."

We accepted that in the battle near the Crimean, the losses of the "Great" army amounted to four thousand people. The rationale for this choice will be given below.

The column "Hypothetical strength" shows the number of soldiers who would have remained in the ranks if there were no combat losses, and detachments for protection would not have been allocated, that is, if the size of the army was reduced only because of the difficulties of the march. Then the hypothetical strength of the center of the army should be a smooth, monotonically decreasing curve, and it can be approximated by some function n (t).

Suppose that the rate of change of the approximating function is directly proportional to its current value, that is

dn / dt \u003d - λn.

Then

n (t) \u003d n0 e- λ t,

where n0 is the initial number of troops, n0 \u003d 301 thousand.

The hypothetical number is related to the real one - it is the sum of the real number with the number of troops allocated for protection, as well as with the amount of losses in battles. But we must take into account that if there were no battles, and the soldiers remained in the ranks, then their number would also decrease over time at the rate at which the size of the entire army was reduced. For example, if there were no battles and no guards were allocated, then in Moscow there would be

90 + (12 e- 23 λ + 30) e- 8 λ + 4 + 13 \u003d 144.3 thousand soldiers.

The odds for λ are the number of days that have passed since this battle.

The parameter λ is found from the condition

Σ (n (ti) - ni) 2 \u003d min, (1)

where ni is taken from the line "Hypothetical number", ti is the number of days in a day from the moment of crossing the border.

Relative losses per day is a value that characterizes the rate of change in the hypothetical population. It is calculated as the logarithm of the ratio of the number at the beginning and at the end of a given period to the duration of this period. For example, for the first period:

ln (301 / 195.5) / 52 \u003d 0.00830 1 / day

Attention is drawn to the high intensity of non-combat losses in the pursuit of the Russian army from the border to Smolensk. On the transition from Smolensk to Borodino, the intensity of losses decreases by 20%, this is obviously due to the fact that the rate of pursuit has decreased. But on the way from Borodino to Moscow, the intensity, we emphasize, of non-combat losses increases two and a half times. The sources do not mention any epidemics that would cause increased morbidity and mortality. This once again suggests that the value of losses of the "Great" army in the Battle of Borodino, which according to Denier is 30 thousand, is underestimated.

Again, we will proceed from the fact that the size of the "Great" army in the Borodino field was 185 thousand, and its losses - 58 thousand. But at the same time we are faced with a contradiction: according to Table 9, there were 130 thousand Napoleonic soldiers and officers on the Borodino field. This contradiction, in our opinion, is removed by the following assumption.

The General Staff of the Napoleonic army recorded the number of soldiers who crossed the border with Napoleon on June 24, according to one statement, and suitable reinforcements - according to another. It is a fact that reinforcements were coming. In a report to Emperor Alexander of August 23 (September 4, NS), Kutuzov wrote: “Yesterday several officers and sixty privates were taken prisoners. According to the numbers of the corps to which these prisoners belong, it is doubtless that the enemy is concentrated. The fifth battalions of the French regiments subsequently arrive to him. "

According to Clausewitz, "during the campaign, 33,000 men came with Marshal Victor, 27,000 with the divisions of Durutte and Loison, and 80,000 other reinforcements, hence about 140,000." Marshal Victor and the divisions of Durutte and Loison joined the "Great" army a long time after it left Moscow, and could not participate in the Battle of Borodino.

Of course, the number of reinforcements on the march was also declining, so of the 80 thousand soldiers who crossed the border, Borodin reached

185 - 130 \u003d 55 thousand top-ups.

Then we can assert that on the Borodino field there were 130 thousand soldiers of the "Great" army itself, as well as 55 thousand reinforcements, the presence of which remained "in the shadows", and that the total number of Napoleon's troops should be taken equal to 185 thousand people. Let us assume that the losses are proportional to the number of troops directly involved in the battle. Provided that 18 thousand remained in the reserve of the "Great" Army, the recorded losses amount to

58 (130 - 18) / (185 - 18) \u003d 39 thousand.

This value agrees surprisingly well with the data of the French General Segur and a number of other researchers. We will assume that their assessment is more consistent with reality, that is, we will assume that the amount of recorded losses is 40 thousand people. In this case, "shadow" losses will be

58 - 40 \u003d 18 thousand people.

Therefore, we can assume that in the Napoleonic army, double-entry bookkeeping was carried out: some of the soldiers went through one list, some - according to others. This applies to both the total number of the army and its losses.

With the found value of the accounted losses, condition (1) is fulfilled with the approximation parameter λ equal to 0.00804 1 / day and the value of losses in the battle at Krymskiy - 4 thousand soldiers and officers. In this case, the approximating function approximates the value of hypothetical losses with a sufficiently high accuracy of the order of 2%. This accuracy of the approximation indicates the validity of the assumption that the rate of change of the approximating function is directly proportional to its current value.

Using the results obtained, create a new table:

Table 12. The size of the center of the "Great" army

Tab. 12

We now see that the relative losses per day are in fairly good agreement with each other.

With λ \u003d 0.00804 1 / day, daily non-combat losses were 2,400 at the beginning of the campaign and slightly more than 800 people per day when approaching Moscow.

To be able to take a closer look at the Battle of Borodino, we proposed a numerical model of the dynamics of the losses of both armies in the Battle of Borodino. The mathematical model provides additional material for analyzing whether a given set of initial conditions corresponds to reality or not, helps to discard extreme points, and also to choose the most realistic option.

We assumed that the losses of one army at a given time are directly proportional to the current strength of the other. Of course, we are aware that such a model is highly imperfect. It does not take into account the division of the army into infantry, cavalry and artillery, it also does not take into account such important factors as the talent of commanders, the valor and military skill of soldiers and officers, the effectiveness of command and control of troops, their equipment, etc. But, since opponents of approximately equal level opposed each other, even such an imperfect model will give qualitatively plausible results.

Based on this assumption, we obtain a system of two ordinary linear differential equations of the first order:

dx / dt \u003d - py

dy / dt \u003d - qx

The initial conditions are x0 and y0 - the number of armies before the battle and the amount of their losses at the time t0 \u003d 0: x'0 \u003d - py0; y'0 \u003d - qx0.

The battle lasted until darkness, but the most bloody actions, which brought the greatest number of losses, continued in fact until the capture of Raevsky's battery by the French, then the intensity of the battle subsided. Therefore, we will assume that the active phase of the battle lasted ten hours.

Solving this system, we find the dependence of the size of each army on time, and also, knowing the losses of each army, the proportionality coefficients, that is, the intensity with which the soldiers of one army hit the soldiers of the other.

x \u003d x0 ch (ωt) - p y0 sh (ωt) / ω

y \u003d y0 ch (ωt) - q x0 sh (ωt) / ω,

where ω \u003d (pq) ½.

The table 7 below presents data on losses, the number of troops before and after the beginning of the battle, taken from various sources. The data on the intensity, as well as on the losses in the first and last hour of the battle, were obtained from the mathematical model we proposed.

When analyzing the numerical data, we must proceed from the fact that opposing each other were opponents approximately equal in training, technique and high professional level of both ordinary soldiers and officers and army commanders. But we must also take into account the fact that “Under Borodino, it was a matter - to be or not to be Russia. This battle is our own, our own battle. In this sacred lottery, we were the contributors of everything inseparable from our political existence: all our past glory, all our true national honor, national pride, the greatness of the Russian name - all our future destiny. "

In the course of a fierce battle with a numerically superior enemy, the Russian army retreated somewhat, maintaining order, command, artillery and combat capability. The attacking side suffers greater losses than the defending side until it defeats its opponent and he turns to flight. But the Russian army did not flinch and did not run.

This circumstance gives us reason to believe that the total losses of the Russian army should be less than the losses of the Napoleonic one. One cannot but take into account such an intangible factor as the spirit of the army, to which the great Russian commanders attached so much importance, and which Leo Tolstoy so subtly noted. It is expressed in valor, fortitude, the ability to defeat the enemy. We can, of course, conditionally, assume that this factor in our model is reflected in the intensity with which the soldiers of one army defeat the soldiers of another.

Table 13. Number of troops and losses of the sides

Tab. thirteen

The first line of Table 13 shows the values \u200b\u200bof the initial strength and losses indicated in the Bulletin No. 18 of the "Great Army" issued by Napoleon. With such a ratio of the initial number and the amount of losses, according to our model, it turns out that during the battle the losses of the Russian army would be 3-4 times higher than the losses of the Napoleonic one, and the Napoleonic soldiers fought three times more effectively than the Russians. With such a course of battle, it would seem that the Russian army should have been defeated, but this did not happen. Therefore, this set of initial data is not true and should be rejected.

The next line presents the results based on data from French professors Lavisse and Rambeau. As our model shows, the losses of the Russian army would be almost three and a half times greater than the losses of Napoleon. In the last hour of the battle, the Napoleonic army would have lost less than 2% of its strength, and the Russian more than 12%.

The question arises, why did Napoleon stop the battle if the Russian army was soon to be defeated? This is contradicted by eyewitness accounts. We present the testimony of Caulaincourt about the events that followed the capture of the Raevsky battery by the French, as a result of which the Russian army was forced to retreat.

“A sparse forest covered their passage and hid their movements in this place from us. The emperor hoped that the Russians would speed up their retreat, and counted on throwing his cavalry on them in order to try to break the line of the enemy troops. Parts of the Young Guard and the Poles were already moving to approach the fortifications that remained in Russian hands. The emperor, in order to better see their movements, went ahead and walked all the way to the very line of the riflemen. Bullets whistled around him; he left his retinue behind. The emperor was at this moment in great danger, since the firing became so hot that the Neapolitan king and several generals rushed to persuade and beg the emperor to leave.

The emperor then went to the approaching columns. The old guard followed; carabinieri and cavalry marched in echelons. The emperor, apparently, decided to capture the last enemy fortifications, but the prince of Neuchâtel and the king of Naples pointed out to him that these troops did not have a commander, that almost all divisions and many regiments also lost their commanders, who were killed or wounded; the number of cavalry and infantry regiments, as the emperor can see, has greatly diminished; the time is already late; the enemy is really retreating, but in this order, he maneuvers and defends his position with such courage, although our artillery crushes his army masses that one cannot hope for success unless the old guard is launched into the attack; in this state of affairs, the success achieved at this cost would be a failure, and failure would be such a loss that would negate the gain in the battle; finally, they drew the attention of the emperor to the fact that one should not risk the only corps, which still remains intact, and should be reserved for other occasions. The Emperor hesitated. He rode forward again to observe the enemy's movements for himself. "

The emperor “made sure that the Russians were in positions, and that many corps not only did not retreat, but concentrated together and, apparently, were going to cover the retreat of the rest of the troops. All reports that followed one after another said that our losses were very significant. The emperor made a decision. He canceled the order to attack and limited himself to an order to support the corps still waging a battle in case the enemy tried to do something that was unlikely, for he also suffered enormous losses. The battle ended only at nightfall. Both sides were so tired that at many points the shooting stopped without a command. "

The third line contains the data of General Mikhnevich. The very high losses of the Russian army are striking. The loss of more than half of its initial staff cannot be sustained by any army, even the Russian one. In addition, estimates of modern researchers agree that the Russian army lost 44 thousand people in the battle. Therefore, these initial data seem to us untrue and should be discarded.

Consider the data in the fourth line. With such a balance of forces, our proposed model shows that the Napoleonic army fought extremely effectively and inflicted heavy losses on its enemy. Our model allows us to consider some possible situations. If the number of armies were the same, then with the same efficiency, the number of the Russian army would be reduced by 40%, and the Napoleonic one - by 20%. But the facts contradict such assumptions. In the battle at Maloyaroslavets, the forces were equal, and for the Napoleonic army it was not about victory, but about life. Nevertheless, the Napoleonic army was forced to retreat and return to the devastated Smolensk road, dooming itself to hunger and hardship. In addition, we have shown above that the value of losses equal to 30 thousand is underestimated, therefore Vasiliev's data should be excluded from consideration.

According to the data given in the fifth line, the relative losses of the Napoleonic army, amounting to 43%, exceed the relative losses of the Russian army, equal to 37%. It cannot be expected that European soldiers who fought for winter apartments and the opportunity to cash in on the plundering of a defeated country could withstand such high relative losses, exceeding the relative losses of the Russian army, which fought for its Fatherland and defended the Orthodox faith from the atheists. Therefore, although these data are based on the views of modern domestic scientists, nevertheless, they seem unacceptable to us.

Let's move on to considering the data of the sixth line: the number of Napoleon's army is taken equal to 185 thousand, Russian - 120 thousand, losses - 58 and 44 thousand people. According to our model, the losses of the Russian army throughout the battle are somewhat lower than the losses of the Napoleonic army. Let's pay attention to an important detail. The efficiency with which the Russian soldiers fought was twice that of their opponents! The late veteran of the Great Patriotic War, to the question: "What is war?", Answered: "War is work, hard, dangerous work, and it must be done faster and better than the enemy." This is quite consistent with the words of the famous poem by M.Yu. Lermontov:

The enemy experienced a lot that day,

What does Russian fight mean,

Our hand-to-hand combat!

This gives us reason to understand why Napoleon did not send the guard into the fire. The valiant Russian army fought more effectively than its adversary and, despite the inequality of forces, inflicted heavier losses on it. One cannot but take into account the fact that the losses in the last hour of the battle were practically the same. Under such conditions, Napoleon could not count on the defeat of the Russian army, just as he could not exhaust the forces of his army in the battle that had become hopeless. The results of the analysis performed allow us to accept the data presented in the sixth row of Table 13.

So, the number of the Russian army was 120 thousand people, the Napoleonic army - 185 thousand, respectively, the losses of the Russian army - 44 thousand, Napoleonic - 58 thousand.

Now we can create a summary table.

Table 14. The number and losses of the Russian and Napoleonic armies

in the battle of Borodino.

Tab. fourteen

The valor, selflessness, martial art of Russian generals, officers and soldiers who inflicted huge losses on the “Great” army forced Napoleon to abandon the decision to put his last reserve, the Guards Corps, into action at the end of the battle, since even the Guards could not achieve decisive success. He did not expect to meet such exceptionally skillful and fierce resistance from Russian soldiers, because

And we promised to die

And they kept the oath of allegiance

We are in the Borodino battle.

At the end of the battle MI Kutuzov wrote to Alexander I: “This day will remain an eternal monument to the courage and excellent bravery of Russian soldiers, where all the infantry, cavalry and artillery fought desperately. Everyone's desire was to die on the spot and not yield to the enemy. The French army under the leadership of Napoleon himself, being in superb forces, did not overcome the firmness of the spirit of the Russian soldier, who sacrificed his life with vigor for his fatherland. "

Everyone, from a soldier to a general, sacrificed their lives for their country with courage.

“Confirm in all companies,” the chief of artillery Kutaisov wrote on the eve of Borodin, “that they should not withdraw from their position until the enemy has mounted the cannons. To tell the commanders and all gentlemen officers that only by bravely holding on to the closest grape-shot can we achieve that the enemy does not give up a single step of our position.

Artillery must sacrifice itself. Let them take you with the guns, but fire the last shot at point-blank range ... If the battery had been taken for all this, although one can almost vouch for the opposite, it has completely atoned for the loss of the guns ... "

It should be noted that these were not empty words: General Kutaisov himself died in the battle, and the French were able to capture only a dozen and a half guns.

The task of Napoleon in the battle of Borodino, as well as at the stage of the pursuit, was the complete defeat of the Russian army, its destruction. To defeat an enemy approximately equal in level of military skill, a large numerical superiority is required. Napoleon concentrated on the main direction 300 thousand against the Russian army of 120 thousand. Possessing a superiority of 180 thousand at the initial stage, Napoleon could not keep it. “With more care and better organization of the food business, with a more deliberate organization of marches, in which huge masses of troops would not be needlessly piled up on one road, he could prevent the famine that prevailed in his army from the very beginning of the campaign, and thus it would have kept it in a more complete composition. "

Huge non-combat losses, testifying to the neglect of his own soldiers, who for Napoleon were just "cannon fodder", were the reason that in the Battle of Borodino, although he had one and a half superiority, he lacked one or two corps to deliver a decisive blow ... Napoleon was unable to achieve the main goal - the defeat and destruction of the Russian army neither at the stage of pursuit, nor in the Battle of Borodino. Failure to fulfill the tasks facing Napoleon is an indisputable achievement of the Russian army, which, thanks to the skill of command, courage and valor of officers and soldiers, snatched success from the enemy at the first stage of the war, which caused his heavy defeat and complete defeat.

“Of all my battles, the most terrible is the one I gave near Moscow. The French in it showed themselves worthy to win, and the Russians acquired the right to be invincible, ”Napoleon later wrote.

As for the Russian army, in the course of the most difficult, brilliantly conducted strategic retreat, in which not a single rearguard battle was lost, it retained its forces. The tasks that Kutuzov set for himself in the Battle of Borodino - to preserve his army, bleed and deplete Napoleon's army - were just as brilliantly accomplished.

On the Borodino field, the Russian army withstood the one and a half times larger army of Europe united by Napoleon and inflicted significant losses on its enemy. Yes, indeed, the battle near Moscow was "the most terrible" of those given by Napoleon, and he himself admitted that "the Russians acquired the right to be invincible." One cannot but agree with this assessment of the Emperor of France.

Notes:

1 Military encyclopedic lexicon. Part two. SPb. 1838.S. 435-445.

2 P.A. Zhilin. M. Science. 1988 S. 170.

3 Battle of Borodino from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. We have corrected errors in the 4th and 15th lines, in which the compilers rearranged the numbers of the Russian and Napoleonic armies.

4 Artsybashev I.P. Losses of Napoleonic generals on September 5-7, 1812 in the Battle of Borodino.

5 Grunberg P.N. On the size of the Great Army in the battle at Borodino // The era of Napoleonic wars: people, events, ideas. Materials of the V-th All-Russian scientific conference. Moscow April 25, 2002 M. 2002.S. 45-71.

6A. Vasiliev. "Losses of the French army at Borodino" "Rodina", No. 6/7, 1992. P.68-71.

7 Military encyclopedic lexicon. Part two. SPb. 1838.S. 438

8 Robert Wilson. “A diary of travels, services and social events during his stay in European armies during the campaigns of 1812-1813. SPb. 1995 p. 108.

9 According to Shaumbra, from whom we generally borrowed data on the size of the French armed forces, we have determined the size of the French army when it entered Russia at 440,000 people. During the campaign, 33,000 men came up with Marshal Victor, with the divisions of Durutte and Loison - 27,000 and other reinforcements of 80,000 people, therefore, about 140,000 people. The rest consists of transport units. (Clausewitz's note). Clausewitz. A trip to Russia in 1812. Moscow. 1997, p. 153.

10 Clausewitz. A trip to Russia in 1812. Moscow. 1997, p. 153.

11 Armand de Caulaincourt. Memoirs. Smolensk. 1991. p. 69.

12 Armand de Caulaincourt. Memoirs. Smolensk. 1991.S. 70.

13 Armand de Caulaincourt. Memoirs. Smolensk. 1991.S. 77.

14 Armand de Caulaincourt. Memoirs. Smolensk. 1991.S. 177.178.

15 Armand de Caulaincourt. Memoirs. Smolensk. 1991.S. 178.

16 Clausewitz. 1812 year. Moscow. 1997, p. 127.

17 "Rodina", No. 2 of 2005

18 http://ukus.com.ua/ukus/works/view/63

19 Clausewitz. A trip to Russia in 1812. Moscow. 1997 p. 137-138.

20 M.I. Kutuzov. Letters, notes. Moscow. 1989 p. 320.

21 Denis Davydov. Library for reading, 1835, v.12.

22 E. Lavisse, A. Rambeau, "History of the XIX century", M. 1938, v.2, p. 265

23 "Patriotic War and Russian Society". Volume IV.

24 A. Vasiliev. "Losses of the French army at Borodino" "Rodina", No. 6/7, 1992. P.68-71.

25 P.A. Zhilin. M. Science. 1988 S. 170.

26 Armand de Caulaincourt. Memoirs. Smolensk. 1991.S. 128,129.

27 M.I. Kutuzov. Letters, notes. Moscow. 1989 p. 336

28 M. Bragin. Kutuzov. ZhZL. M. 1995.p.116.

29 Clausewitz. 1812 year. Moscow. 1997, p. 122.

Already in Moscow, that this war would turn out for him not a brilliant victory, but a shameful flight from Of Russia mad with horror soldiers of his once great army, which conquered all of Europe? In 1807, after the defeat of the Russian army in the battle with the French at Friedland, Emperor Alexander I was forced to sign the unprofitable and humiliating peace treaty of Tilsit with Napoleon. At that moment, no one thought that in a few years the Russian troops would drive the Napoleonic army to Paris, and Russia would take a leading position in European politics.

In contact with

Classmates

Causes and course of the Patriotic War of 1812

Main reasons

- Violation by both Russia and France of the terms of the Tilsit Treaty. Russia sabotaged the continental blockade of England, which was unprofitable for itself. France, in violation of the treaty, deployed troops in Prussia, annexing the Duchy of Oldenburg.

- The policy towards European states pursued by Napoleon without taking into account the interests of Russia.

- An indirect reason can also be considered the fact that Bonaparte twice attempted to marry the sisters of Alexander the First, but both times he was refused.

Since 1810, both sides have been actively pursuing preparation to war, accumulating military forces.

The beginning of the Patriotic War of 1812

Who, if not Bonaparte, who conquered Europe, could be sure of his blitzkrieg? Napoleon hoped to defeat the Russian army even in border battles. In the early morning of June 24, 1812, the French Grand Army crossed the Russian border in four places.

The northern flank, under the command of Marshal MacDonald, advanced in the direction Riga - St. Petersburg. Main a group of troops under the command of Napoleon himself moved towards Smolensk. South of the main forces, the offensive was developed by the corps of Napoleon's stepson, Eugene de Beauharnais. The corps of Austrian General Karl Schwarzenberg was advancing in the Kiev direction.

The northern flank, under the command of Marshal MacDonald, advanced in the direction Riga - St. Petersburg. Main a group of troops under the command of Napoleon himself moved towards Smolensk. South of the main forces, the offensive was developed by the corps of Napoleon's stepson, Eugene de Beauharnais. The corps of Austrian General Karl Schwarzenberg was advancing in the Kiev direction.

After crossing the border, Napoleon was unable to maintain a high rate of advance. It was not only the huge Russian distances and the famous Russian roads that were to blame. The local population gave the French army a slightly different reception than in Europe. Sabotage the supply of food from the occupied territories became the most massive form of resistance to the invaders, but, of course, only the regular army could provide serious resistance to them.

Before joining Moscow the French army had to participate in nine major battles. In a large number of battles and armed clashes. Even before the occupation of Smolensk, the Great Army lost 100 thousand soldiers, but, in general, the beginning of the Patriotic War of 1812 was extremely unfortunate for the Russian army.

On the eve of the invasion of the Napoleonic army, Russian troops were dispersed in three places. The first army of Barclay de Tolly was at Vilna, the second army of Bagration was near Volokovysk, and the third army of Tormasov was in Volyn. Strategy Napoleon's idea was to smash the Russian armies separately. Russian troops begin to retreat.

Through the efforts of the so-called Russian party, instead of Barclay de Tolly, MI Kutuzov was appointed to the post of commander-in-chief, who was sympathetic to many generals with Russian surnames. The retreat strategy was not popular in Russian society.

However, Kutuzov continued to adhere to tactics digression chosen by Barclay de Tolly. Napoleon strove to impose on the Russian army the main, general battle as soon as possible.

The main battles of the Patriotic War of 1812

A bloody battle for Smolensk became a rehearsal for a general battle. Bonaparte, hoping that the Russians will concentrate all their forces here, prepares the main attack, and pulls an army of 185,000 to the city. Despite Bagration's objections, Bucklay de Tolly decides to leave Smolensk. The French, having lost more than 20 thousand people in battle, entered the burning and destroyed city. The Russian army, despite the surrender of Smolensk, retained its combat capability.

A bloody battle for Smolensk became a rehearsal for a general battle. Bonaparte, hoping that the Russians will concentrate all their forces here, prepares the main attack, and pulls an army of 185,000 to the city. Despite Bagration's objections, Bucklay de Tolly decides to leave Smolensk. The French, having lost more than 20 thousand people in battle, entered the burning and destroyed city. The Russian army, despite the surrender of Smolensk, retained its combat capability.

News about surrender of Smolensk overtook Kutuzov not far from Vyazma. Meanwhile, Napoleon advanced his army towards Moscow. Kutuzov found himself in a very serious situation. He continued to retreat, but before leaving Moscow, Kutuzov had to give a general battle. The protracted retreat left a depressing impression on the Russian soldiers. Everyone was eager to give a decisive battle. When a little more than a hundred miles remained to Moscow, on the field near the village of Borodino, the Great Army collided, as Bonaparte himself later admitted, with the Invincible army.

Before the start of the battle, Russian troops numbered 120 thousand, the French were 135 thousand. On the left flank of the formation of the Russian troops were Semyonov flashes and parts of the second army Bagration... On the right - the battle formations of the first army of Barclay de Tolly, and the old Smolensk road was covered by the third infantry corps of General Tuchkov.

Before the start of the battle, Russian troops numbered 120 thousand, the French were 135 thousand. On the left flank of the formation of the Russian troops were Semyonov flashes and parts of the second army Bagration... On the right - the battle formations of the first army of Barclay de Tolly, and the old Smolensk road was covered by the third infantry corps of General Tuchkov.